aNERDspective 50- Nurul Syahida

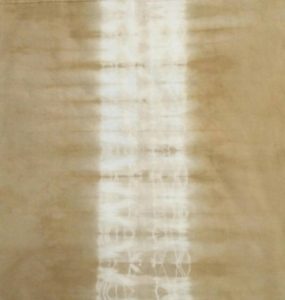

A yellow-brown natural dye tie-dye from an artisan from Kelantan (Photo credit: Nurul Syahida)

Nurul Syahida is an academic researcher and currently is pursuing her doctorate study on natural dyeing practices in local textiles. She has previously done her research on traditional Kelantan gold thread embroidery, also called kelingkan for her Master’s degree. Her interest includes the development of local knowledge through first-hand experiencing as well as direct observation and participation.

In this episode of aNERDspective (our NERD talk show where we converse with amazing friends about their textile adventure and perspectives), we talked to Syahida about how she first fell in love with textiles and how she conducts her research in the area of local wisdom development, preservation and dissemination, especially in local textile and natural dyes.

Note: The transcript has been edited for reading format.

Tony Sugiarta: Welcome Syahida to today’s episode of aNERDspective. How are you doing there in Kelantan?

Nurul Syahida: Hi Tony, nice to meet you. I am good in Kelantan. Even in the pandemic, I am still outdoors and have some of the environment.

It is my first time I am having a guest with an outdoor background which is very refreshing to see. I saw your work when talking to Ummi Junid in one of her podcasts, talking about Malaysian textiles and then we got in touch and I looked through your work which you are currently studying or pursuing PhD in natural dyes and textiles. I would really love to find out more about your perspectives as an academic, researching local wisdom and knowledge transfer and how it is applied to textiles. Before we get into our discussion, maybe you would like to do a little introduction about yourself and how you get in touch with textiles and so on.

First of all, I would like to introduce myself. My name is Nurul Syahida. I am an academic researcher and I am interested in local wisdom-related (topics), especially in traditional textiles and in local practices. Like what you said, I am currently pursuing my study in University Malaysia Kelantan which is located in Kelantan, which I am very grateful to be here.

Actually I was born in Kelantan, studying in Kelantan, and it loaded me with the rich culture of art. (It is) the center of knowledge which I can say is invisible to me at a young age. It only comes when I am directly involved with the academic journey. So, that is how I am involved in local textile.

Actually, I do love the behind the scenes in making textile which is “human’s second skin” because we are actually born naked, so what is the purpose of the textile is to cover us from the weather, a protection of our skin, and everything else. That is a little bit from me and this is my journey of researching textiles.

About the local knowledge as well, I have involved some of the indigenous people to transfer the knowledge about how to dye the textile, how to process the dye from their own surroundings and apply that to the textiles. It can be to generate their income or some sort of tourist attraction and instead of that, we want the local knowledge to flourish and to always be practiced. It is not only for the local practitioners, it is also for everyone who is interested in that.

Textile is like “human’s second skin” because we are actually born naked. The purpose of the textile is to cover us from the weather, a protection of our skin, and everything else.

I like that you describe that as a human’s second skin. How do you get in touch with textiles in the first place?

Actually, it is about curiosity. It started from my childhood (when) my mother was a tailor. She got a lot of textiles. So, I was just looking at that, what is this pattern? My sister and mum were just wearing sarong, and I asked them why they were only wearing sarong without any top? I am just curious. I do not have the answers. I do not have the sources that share the knowledge about the process. I just know from the environment. When I was pursuing my degree, when I went to see my lecturer, she just said, “go and explore. Go and access the workplace and get in touch with the senior and the practitioner.”

I was just reading and then curiosity just came. The access was there and I just explore. It is nice. Then, I am going into the history and the people who practice that. That brings me to the next level for Master’s study. The major for my study is batik practices and for my master, I go to gold thread embroidery practice in Kelantan which is called kelingkan. For my PhD, I am also pursuing the practices but I am into the natural dyes practice.

So, it is literally that Kelantan is the backyard. I mean the knowledge of textiles in your backyard which you just go out to explore. Really lucky.

How many practitioners are there in Kelantan or textiles in general?

Actually, we can categorise into several, such as songket and kelingkan itself. Batik I can say that there are too many people, there are too many practitioners, but as I go through, we have to decide which is (the one who) really practice or only vendors. Because actually they can talk about batik like they are doing. So, sometimes they are not really doing batik, they just know it.

I can say, there are many practitioners in batik making, but (not many) doing natural dyeing process practitioners. That is the major, we have songket tenun (weaving), batik, and gold thread embroidery.

Mostly are in batik?

Yes.

And just a very small fraction of that does natural dyes?

Yes.

In Kelantan especially, I can categorise that they are practicing three types of dyeing process with the most practised is Rhemasol dyeing process, the second one is Napthol dyeing process, and the least is natural dyeing process.

I can say, I only found a few local Kelantanse practitioners who purely practice the natural dyes. They are doing this kind of dyeing process not because they are neglecting the environment, but because they lack knowledge in sustainable management implementation, and it is costly to handle the waste. And they want the fast process, of course.

It is quite sad for me when I approach the practitioners who practice with the chemical. I can see their hands got harmed because of the twenty to thirty years of experience. It is kind of painful for me because they want to preserve the heritage but they have to suffer for it. We have to come up with an alternative that you can reduce. We cannot (eliminate) all the chemical processes, but we can reduce the detriment to them.

For those you mentioned are practicing natural dyes, are they already practicing for a long time like a knowledge that has been passed down from their parents or grandparents, or is it something that they just recently picked up?

For those who I have met, he was practicing. He is the initiator for natural dyeing. His passion is the dyeing process which he loves to explore. Nowadays, he passed it down to his daughter, the second generation. What intrigues my interest here is that he studied on his own (through a) medical perspective, natural dyes from a medical perspective. But he cannot get the recognition because he has no scientific research, no medical certificate, but he tests his surroundings. One of the things I can share is that he uses turmeric to dye the textile and turmeric has something that it can cover the fever. But unfortunately, it is not going to be easy to get some sharing from him because I am not his relative. I am not sure but he is not sharing his documentation.

Interesting that he approached it from textile and medicinal properties.

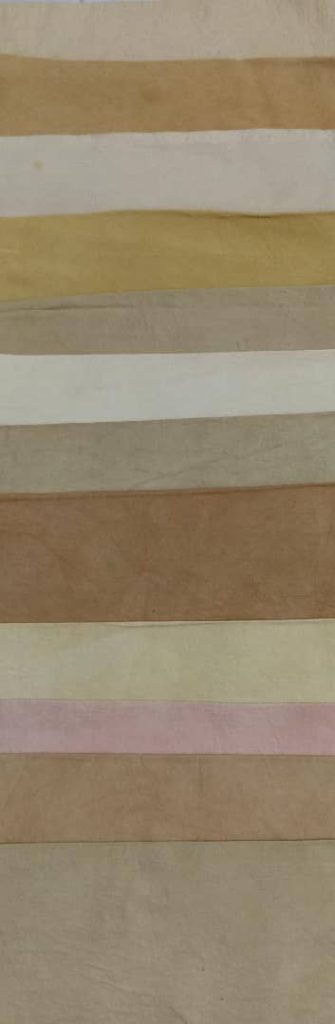

Results of natural dye colours from Kelantan, including mahogany leaves, mangosteen leaves, Morinda citrifolia (mengkudu) roots, mango leaves, mangrove bark, Dillenia suffruticosa (Daun Simpoh Air) leaves.

Probably asking more about your research in terms of your research process. If you can share a little bit of your process, from the ideation, research methodology, and how did you approach the subject?

Before that, I would like to give an overview, what draws this research topic. Actually, I have got interested in culture construct which is a construct from seven elements, which are social organisation, language, economy, religion, knowledge system, technology, and artefacts. These elements, when they have been paired, when they are merged, they used to become something. For example, the language and artefact, those two elements can give the semantic element which can give meaning behind the textile and motif itself.

For my study, I go to the local wisdom from knowledge systems and also the technology. So, it creates the local wisdom there, sometimes we call some tribes for their indigenious knowledge. There is interaction between humans and the environment. That is interesting for me because that becomes an issue of sustainability and preservation nowadays. We want to preserve heritage, we want to sustain our environment, we love them all but we are still practicing the chemical dyeing process. This is the kick off of my study about the technology and natural dyes that I am (exploring) in my ongoing thesis.

I am looking for the term “technology” which nowadays people would say that technology is about the current technology, using machinery. But they forgot that without traditional technology, there is no current technology. So, this kind of technology, it is a production matter of emergence skills and technique.

In my research, there is probably my idea from the culture view and then I go to the issue. I approach the practitioners, as I decide that from the literature. We can say that the gap between the practitioners, the academician, and the consumer, is very huge. There are a lot of studies saying that natural dyes can be revived by innovation. They said you can use the freeze drying method, spray drying method, and they find out how to cut off the local knowledge process itself.

The local knowledge, or local wisdom itself has a few keywords that we can emphasize. I got interested in the keywords that I have here. It is a process of experience but in Malay we can put it as pengalaman, that is how we can interpret the natural knowledge itself. That is natural dyes (zat warna alam in Malay). That is interesting. That it is the process of experience.

The second one is the everyday routine for the locals. That is why they do not have a systematic way to measure their own dyes. They are problem solvers. When they have to fix the textile, they want the textile to become very vivid colours, they explore more and solve the problem.

Then, they use medium-way processes and tools. We cannot call that a long process, like a trial and error process. They enjoy doing that. When I was doing my own observation, one of the approaches or methods was to interview, observe, and participate. What is interesting is that I cannot just interview because they want us to practice. One of the things I am grateful for is that I can speak Kelantanese (a local Kelantan dialect) and that is more comfortable for them. When I approached them, they said that I can just come to their house and see the process.

When I go to their house, I cannot just observe but I have to practice, experience that and make mistakes. It is very tiring actually doing natural dyes because we have to endure it from the morning until the evening, maybe until night.

So, I just experienced it and hung in there. I have learnt from the literature about the process of the natural dyes. When we are with them, they are sharing something that is precious to us. We have to appreciate what they have experienced. For example, he said to me, “Just take that (from the surroundings) and put it on the pot and you just boil it.”

I just said, in my heart, “will this leaf give you a colour?”

Then I just follow the flow and he just shows the process, takes the fabric, and soaks it. I just like, “is that it? Is it the process?”

He got the colour and said it is okay and it can be the background and fill with the pattern after that. They are exploring, they are accepting because natural dyes give you very surprising and very disappointing colours. From the way they appreciate that, they do not worry about the process and just enjoy it. When you make the textile, you do not have to worry because there will be an owner. Sometimes I get afraid that if I am doing textile with this kind of range of colour, not a very vivid, dark colour, people will hate this. But for them, once you have the textile, it already has an owner. That is very interesting for me.

They are accepting because natural dyes give you very surprising and (sometimes,) very disappointing colours. From the way they appreciate that, they do not worry about the process and just enjoy it.

Definitely, because we tend to put textiles with commercial value, what the customers demand and there are colour ranges that we need to achieve and to improve. This is very interesting the way they look at textiles, the casual response to it that there is an owner that has been chosen by someone up there. You mentioned something about local wisdom which I find to be a very interesting concept, because I think in Bahasa Indonesia they call it kearifan lokal. Is that what you call it in Bahasa Melayu as well?

We call it kearifan tempatan.

Probably in the older generation is just wisdom. And now we “localize” it because that is a treasure in the particular area. You mentioned earlier that the man is not sharing as much because you are not essentially a family member. How do you actually interact with that?

That is an interesting thing to ask, about how I connect with the local practitioners. Actually, it is not a one day or half-day communication with them. I actually go to them one day, two days, one week, two weeks, and keep in touch with them. Sometimes we talk about non-related dyeing processes but we listen to their own struggle nowadays. When we listen to them, they are willing to share something with us. It is not because we want something and we go to them, but for me it is humanistic. When we go to them, we want to learn. For the local practitioners, especially for the locals, they love people who want to study and learn because we will listen to them without any complaint and they are willing to share.

One of the practitioners said to me when I was sitting on the yard in his place, “look at the tree. What colour can that leaf give?”

I said that I do not know because all the leaves have green colour.

He said that you need to look into the surroundings of the fallen leaves, (meaning the plant) has roots. Then you have to know what type of soil is used for those particular trees there. So, you have an idea when you are making natural dyes. You can take the colour and you can say that this kind of leaves with acidic or alkaline (environment), you can have this kind of colour.

When I am walking around, I am not just looking only at the leaves as before, I am looking at the bottom where it falls off. It is very interesting that they can connect that kind of experience and knowledge. Sometimes, I think that we are only looking upwards and not looking at the bottom.

What sort of plants do they normally use for natural dyeing?

Here, we can say that they are using very common materials (from the nearest surrounding) because they also say that they do not want to harm the environment. (They are aware that) when they collect (materials), it can harm some plants. So (it is when) the community themselves want to clear the place and then they go and get the materials. One is mango leaves, (another) one is catappa from the seaside. We have turmeric. I can say that turmeric is the core of colours, like additional flavor for their practice because it has a very vivid colour. So they just dip it into the last process to get the colour.

Generally they use the surrounding materials such as leaves. Some workshops in Pahang also work on the soil, which is bauxite. They use bauxite to make dye. But in Kelantan, we are not using soil, we are all using plant-related dyes.

Do they actually do this to sell or just for exploration?

Some of them are doing this to sell, some of them doing this for exploration. It actually became a selling after that because after more exploration for the colours, it became interesting so (some) wants to buy it. They actually sell them to gain the money, but it is actually the exploration itself. They explore the technique, the process.

The second part of your research is on knowledge transfer. So how would you encourage these practitioners in terms of knowledge documentation and so on?

Knowledge transfer can be practical, in terms of knowledge dissemination, and the second one is about the practical. For me, I can see that knowledge dissemination would like to be emphasized (first) because natural dyes (could) become one community identity or the state identity. The identity of the community will fade when no one or a few can tell about your culture process, about the process of the artefact. So the knowledge dissemination is first.

Sometimes we go to the community that does not know anything about batik, like we go to indigenous people in Jeli and we give the knowledge about batik first. After that when they know about batik, they will ask about the process. At the same time, we have transferred the knowledge. They have the skill and then they will develop their own technology based on their surroundings. That is what we want in the chain of knowledge transfer.

So it is kind of there is a certain entry point, for example you use batik and then expand onto the other aspects of knowledge in terms of expansion of the batik technique itself, like the waxing or whether cap, tulis and so on, as well as the dyeing that they can explore and adapt it locally?

That is the point. People will not know the process when they just see the textile, just for the experience. People will say that batik is very expensive but why are they very expensive. They can only be worn for one year and then it will probably shrink because our body is not in the diet anymore. I have the experience of getting mad with this kind of situation.

They do not know the value of the process, the sweat of the person doing that, the idea and the expression of the pattern that they put into the surface as the decoration of the textile.

I am very open to say that if the new generation or someone who wants to know about the local textile, it is okay if they know that this is a printed one, this is the original one, and this is from machinery one. Just know that there is a local textile and there are various technologies implied nowadays. So they can categorize the type of the textile they have. They will say why this textile is cheaper than this one or what the quality is. So they will go through the process. They can differentiate between the handmade and machinery-made, this kind of knowledge dissemination first.

You mentioned earlier about the knowledge gap between the academia, the practitioners and the consumers that is very huge and I think one, similar to the one that you just touched upon, which is the information dissemination that could help the consumers to understand more about textiles. In terms of, for example technology research and practitioners as you mentioned, there are technologies such as drying technique, freeze dry, etc., how would that be transferred or applied to practitioners? How can we bridge this gap between laboratory research and practical use?

They never go to the local practitioners. They are only doing research at the laboratory. When we asked about why we are not going to the local, this is that they (ed.: the local practitioners) do not want the change. It is actually, we can say that, a stigma. They love to have some approach but they also have the obstacle in which they do not have money or funding because they cannot set up the machinery.

In the laboratory, there is a kind of procedure or SOP in the making process. They are not doing (what the practitioners do) because in the laboratory, they only use the small samples. The laboratory only works on themselves and then in terms of local practitioners, they are doing their practice.

A laboratory person, who practices the local (dyeing process), actually gave me a thought. For example, to treat the fabric, to know the colour fastness of the fabric which is good or not, or to use a normal soap to know the washing fastness. So it is kind of following some kind of SOP, actually she combined between laboratory and local practices, in terms of using the surrounding. But when it comes to the commercial or practitioners, they are saying that it is okay, the colour will stay that way, so there are different procedures at the end. They are just looking for exploration, they are just looking for the colours.

I will say that there is no interconnection between the practices enhancing the natural dyeing colours value, but it is ok. I wish someday we can produce something from a place with emerging local knowledge practices with laboratories.

Essentially technologies could be applied to something else. It would be nice if they were together, but technology could be applied to other sectors as well.

I agree with your point that it can be used in other parts of the arts. I can categorize three types of practitioners, which are local practitioners, contemporary practitioners and also the academicians. There cannot be a merge for the practice process because they have their own strengths. They have their own knowledge. That has been built for 30 to 40 to 50 years. The diversity of knowledge means to respect each other’s knowledge and so we have a variety of innovations.

I agree totally in terms of diversity.

What are some of the challenges that you face during your research?

It can be, first, the humanistic side and, second, the practical side.

For the first one, the humanistic side, I can say (in terms of) approach the practitioners. As I said earlier, to approach them I have to use the dialect. We have to learn, we have to see, we have to eat with them, drink with them and just know all the things about their family. So I know their daughter, their son, and the neighbours. We listened and we want to know their environment. They want to pass their knowledge to the next generation. So we have to look forward to that too.

That is not a challenge actually. It is an opportunity for me to get in touch with them. I would overcome this with the snowball method, which is I know this person and then contact the person he mentioned and then the second one mentions and then I go to the third one. So, we call them the snowball method. That is how I overcame the obstacle. I do not know who practices natural dye, who practices batik making, who practices the method dyeing process. So I got into the snowballs of information.

The second challenge I faced was how to feel the practice of the natural dyeing process myself. Doing things in front of our teacher is very challenging, stressful. I thought about what they are feeling with this slow process. For them, they are experts, so they can just dip there, boil there, just a small matter for them. But for me, it is very stressful to follow their SOP, but when it comes to the practice, I will (need to) practice on my own by referring to the step, try and error process actually.

In Kelantan, among practitioners that I have met, I observe that they only have post-mordanting methods and they rarely or seldom use pre-mordanting or simultaneous mordanting. So that is the kind of knowledge that the laboratory does not pass to them. Maybe they use the process, but that is a very small chance to use the process. When I am doing the exploration myself, pre-mordanting and simultaneous mordanting actually give colours. It will give actually three different range colours by doing these three practices. But for the practitioners, they are looking for the final (process) that gives a very vivid colour because pre-mordanting usually gives a very faded colour and simultaneous (mordanting) is not very stable – sometimes it gives surprising colour range, sometimes it gives a very dull colour.

So it seems that the things that you do is to build rapport and familiarity and also one of the interesting points is probably that you can bring in some of this knowledge from academia and discuss it with them, which I think is very interesting.

What materials do you use for the pre mordanting and simultaneous mordanting?

For the mordanting, the first thing I have identified is the element of technology practice in the natural dyeing process which comes with the extraction, mordanting and dyeing. When it comes to the laboratory approach, they have colour measurement and also colour fasting but when we identify the elements that natural dyeing practice, they can manipulate (the mordanting).

They practice chemical mordant, which is sulphate and copper. It can be replaced with the bio mordant actually but they are not using it. The citrus and belimbing wuluh are the bio mordant they can actually use. They can also use other colours to become the mordant. But they are not doing that anymore. They just purchased the mordant at the chemical suppliers and then they see that citrate is similar to this. This is the element of technology I have identified in this process.

We can expect the process to be manipulated by the practitioners, by the innovators. For example, we can say that the extractor or the innovator or the researcher can manipulate the process that is different from the locals. If they are time consuming, they can use an oven or pressure cooker to overheat the materials.

In terms of mordanting, they can use bio mordant, such as coal. Charcoal from the gelam tree or we can use banana trees or bark, can be used. That is one of the processes they do not explore yet. For them, the exploration is for the colours first, not mordanting. It is ok if the mordanting is with the chemicals. That is the way we see the elements of technology in the natural dyeing process.

Yes. Definitely it is a whole spectrum. You cannot just explore everything at one go so it is kind of a step by step thing.

What are some of the opportunities and threats that you see in terms of natural dyeing in Malaysia?

One of the opportunities I can see is the innovation study that enhances the process dyeing without neglecting the environment and also the practitioners itself. One of the reports says that in 2020, 60% of humans are allergic to chemical dyestuffs. So it is kind of worrying because every day we face chemical things and we try to not eliminate them but to reduce them for our own sake, for our practitioners, for the consumers and environment.

Very interesting and definitely I can see the huge opportunities there.

How far along in your research or how many more years to go for your PhD?

I am on the stage in writing and also to populate my data with the practitioners.

So I would guess that in the near future you will have to complete your thesis. Do you have any final closing conclusion?

For the conclusion, I hope for the local textile and natural dyes to have a kind of identity in the future. While I was doing the research, I also saw the history of Encik Siti Wan Kembang, and her attire. I also know that Thailand also has women’s leadership, while Indonesia too with their own colours. It is interesting because we can portray these women’s leadership through textiles and the colours, especially the natural dyeing process. It is interesting. Maybe someone with a history background? I am only looking at the surface, so I just know a little bit.

I hope for the local textile and natural dyes to have a kind of identity in the future.

Also, when we are putting the meaning behind the artwork, instead of focusing on the production or academic gain, it is a kind of value added for us. We can use the elements of culture, language and artefacts. For the artisan itself, we would never have noticed the textile without surface decoration done by the artist. The textile with the plain white colour, will only be seen as a white colour by many, but the artisans give the expression.

Behind the scenes, they have the process. Not only (to affirm) resurgence of the precious local knowledge, but also to give an affirmative nod towards the developing identity through local knowledge, skills and also the technology itself.

Very nicely summed up, in terms of how we perceive the knowledge transferred and how we can build identities and technologies that are suited to our localities or environment and surroundings.

We hope you enjoyed this episode of aNERDspective. Check out the previous episode on IGTV and our gallery and store if you would like a piece of Indonesia for your home or wardrobe.

Photo credit: Nurul Syahida, unless stated otherwise.

CONTACT US | TERMS OF USE | PRIVACY POLICY

© 2024. NERD VENTURES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

0 Comments