aNERDspective 36 – Sonja Dahl

I’ll Tie My Cloth to Your Cloth, one of Sonja Dahl’s works involving indigo and batik. (Source: Sonja Dahl)

Sonja Dahl is an artist, writer and lecturer of contemporary art at University of Oregon. Her ongoing engagements in Indonesia began in 2012 with her Fulbright Fellowship and Asian Cultural Council-supported arts research projects exploring the cultural significance of textiles as they evolve, hybridise and collapse the boundaries between tradition and the contemporary. Being a contemporary artist herself, Sonja also spent much of her research periods in Yogyakarta immersed in and writing about the culture of collaboration, artist collectives and participatory art in Yogya’s contemporary arts communities.

In this episode of aNERDspective (our NERD talk show where we converse with amazing friends about their textile adventure and perspectives), we caught up with Sonja as she shared what she learnt about the Indonesian’s art scene and the our indigo rituals, a question that comes from one of Sonja’s art works that caught our eyes.

Note: This transcript has been edited for reading format.

Tony Sugiarta (TS): Thank you so much, Sonja for doing this again. How are you doing?

Sonja Dahl (SD): I am doing really well. Now as the season is changing here in Oregon and, sometimes, there is more sunshine, so that has been very nice.

Nice. Has it been back to normal with the pandemic?

Not really. People are still very careful, the number of cases are decreasing right now all over the US so that has been good. People feel a little bit more free, but we are all wearing masks and, mostly staying home a lot of the time, just to be safe. Soon, we will have the opportunity for vaccination. So that will be really wonderful. I cannot wait.

Yes, me too. I cannot wait to explore the world again.

I miss all the nongkrong (hanging out) that I used to have.

So, we met during a chat with Meet the Makers on the creative process of Nusantara. One particular artwork caught my eye because I was researching natural dyes culture. I just would like to find out more about inspiration or intersections that I might use.

Probably we can start with a little introduction about who Sonja is and a little bit about your practice.

I work in many different ways. I am an artist. I am an American, I live in Oregon in the United States. I grew up in Canada. I have lived in Indonesia and I did study abroad when I was in college, in Italy.

I have lived in a number of different places and I think that has really formed my life, how I think of myself. I am primarily an artist, a visual artist. I work with fibers and textiles. Sometimes with the actual cloth as the material, sometimes I make more experimental artworks, use something like indigo dye, but with something you would not normally dye with indigo, like bread or rice, and then making large sort of installations out of that. But I work in many different ways. As is typical, I think for a lot of contemporary artists.

I am also a writer. I publish my writing sometimes. I am also an academic. I teach at the University of Oregon. I teach two lecture classes about contemporary art and the creative process. I work in a lot of different ways. I am sort of spreading out my energy among those different vocations.

Textiles are so intimate. I think they have so much to do with… being a human.

How do you get started with fibers? What draws you into using fibers and textiles?

I made my way into textiles very intuitively. I did not really know what was happening, I think it was a subconscious thing.

Long time ago when I graduated from college, I was making photographs and I was making paintings, but I was starting to get very impatient with the flat two-dimensional surface. And I just started cutting up my paintings, weaving them together and making sort of physical woven creations out of them and collaging photographs. So, it slowly started, I think I just started working my way towards cloth. I have always been drawn to that very primary textile structure of woven cloth. I am interested in textiles because I feel that of all the artistic materials available to us, textiles are so intimate. I think they have so much to do with… being a human. We are so close to them at all times, whether we are wearing them on our bodies or displaying them in our homes, or like the wonderful batiks I see behind you. Humans have, ever since they first began wearing cloth, used textiles, patterns and colours as ways to communicate identity, belonging, ceremonies, rituals. So, I think textiles are just such a rich terrain. I never get bored of researching and making things with cloth.

Interesting. So, you actually get into it almost by accident, like cutting it out and then weaving them.

I learnt how to weave at a retreat center. I went to one when I was in college. That was run all on volunteers. That was a sort of spiritual retreat center and I went to volunteer in a village on a mountain. And they ended up asking me to work in the arts and crafts area. And the first thing I had to learn how to do was to warp a loom. They had all these looms and people would come to be on retreat and they would weave some dish towels to bring home. So, I first learned how to weave and it was also kind of by accident. I did not go there planning to learn that, but something about it just really stuck with me. So, I kept kind of coming back to that. Maybe that was subconsciously why I started weaving my paintings together too.

Is there a huge indigo culture in the US or how do you get interested in it?

I wish that I remembered clearly what the first spark was, but I think it was the colour. I think I was attracted to the colour, the sort of that deep, rich blue. It is sort of the blue of the night sky just when it is becoming night. So, I think it was the colour.

Then I was aware that there was a natural dye and I was starting to get interested in natural dyes. So, not just indigo, but any number of different plants that you can boil and make dyes out of. I started researching indigo dye and I had no idea that it was a living substance. That it was a fermentation. That there were all these associations with it. So, I took a class on natural dyes at my local community college, so that I could learn how to use indigo dye. But that was the beginning.

Was there a huge interest in indigo over there?

Well, in the US, actually over the last, I think maybe 10 years or so, I have seen a huge amount of interest growing. When I was first starting to learn about it, or maybe I just did not know enough, I was not connected enough with the larger scene. I was not finding a lot of information, I was not finding a lot of people talking about or sharing on the internet about indigo dye, but I think in the last 10 years or so, there has been a lot of interest in people not only using Indigo dye, but also growing the plants from seed and learning how to process them properly, which was really hard. When I say a lot, it is not a huge portion of the population, but for something as obscure as this strange dye there has been a lot of interest in recent years. I think it has something to do with people desiring magic in their lives or something, because indigo is so magical. You put a white cloth into it, it comes up green and it just turns blue in the air. It is amazing. So, many people are teaching indigo workshops and a lot of research is being done. So interesting.

In the US, our relationship here to indigo is mostly through the colonial era. When people from Europe were coming over and taking over the land from the indigenous people who actually lived here and then building plantations. We are very famous for the era of cotton plantations, and rice, and indigo dye was another crop that was very profitable. That is a very difficult history because it is related to the Transatlantic slave trade – some of the parts of our national history we are not so proud of. But indigo was grown in the US as one of the early kinds of plantation crops.

Interestingly we do share almost a very similar history. How indigo is one of the most prized possessions that was being traded off. And then it is definitely making a comeback in the scene partly because of the sustainable awareness and we are going back to natural dyes.

It was interesting. It has been five years since the last time I actually spent time in Indonesia, which is so long. But even then, even in 2016, the last time I was there, I really did see a lot of people, a lot of more interest in sustainable natural materials. I also found a lot of people, when I was traveling around Indonesia and talking to weavers and dyers and artists, there was a lot of interest in sort of relearning and reclaiming traditional art forms that had been interrupted by the colonial period. The Dutch brought the synthetic dyes and “oh, why not use these, these are so easy and you can get such beautiful colours”. But when you stop using the natural dyes and cut down all the dye trees and the plants, then your tradition sort of gets cut off. That is happening all over the world, in the United States too.

Is that also about the same period where you discover Indonesia? How do you end up in Indonesia?

That is also a really good question.

No, that came much later. It also began very randomly, but through a scholarship. I was in school again for a short period. I was very interested in indigo dye at the time. So, I had already started working with indigo dye and this was maybe around 2009. I started working with indigo maybe in 2007. So, it has been a long time. I was making all these things with indigo dye and everyone was always asking me, why is this blue stuff so important? I got so tired of having to try and to articulate, why does this dye matter so much to me and why should anyone else care? So, my mentor was trying to help me find resources.

He shared an anthropological article by a woman named Janet Hoskins, who had spent her life’s work living in Sumba, Eastern Indonesia. She wrote this beautiful article about the indigo dye culture, the female-centered indigo dye culture in areas of West Sumba and that article was so influential on my thinking because it opened up my realisation that not just indigo dye itself, but any material is deeply embedded with meanings, cultural significance, with a ritual, and ceremonial significance. She wrote about songs that women would sing that were related to indigo and the way that indigo dyed cloth was used to welcome newborn babies into the world, to wrap them. But it is also used to wrap the bodies of people who had died when they go to the afterlife or to their tomb. So, that idea that this is a substance that has something to do with an entire life cycle.

Even though it was not a culture that I belong to, I think just reading about those things opened up a whole, many different ways of thinking about the substance. So, that was maybe the first time I really started thinking about Indonesia. So again, I think that sort of sunk into my consciousness.

When I was in graduate school at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, I decided I wanted to apply for a Fulbright grant to go somewhere in the world, study and expand my awareness of the arts. As I was trying to decide where I would go, it made sense for me to go someplace where I could learn more about indigo dye, the material that I was so invested in. So, I remembered that article and I started doing more research online and in books about indigo dye cultures around Indonesia. I became so fascinated, but then I also thought that I do not want to just go somewhere and pretend to be an anthropologist because I am not. I need to make a project that has something to do with the whole scope of my reality as an artist, as a contemporary artist.

So, I started researching about Indonesian contemporary arts as well and was very interested in how I saw a number of artists using materials and signifiers from their ancestral roots or culturally significant materials like batik or ceramics from Kasongan or wayang shadow puppetry. These art forms have very long histories, but they were using them in the context of contemporary art as something to tell a story in a new way. All those kinds of things drew me to Indonesia, because I felt, if I was going to continue working with indigo dye, I needed to learn something more, to be more culturally sensitive to at least one of the places in the world where it is actually grown and processed and has been for a long time. Many different layers to how I ended up coming to Indonesia. I arrived in 2012 the first time.

When you first came to Indonesia, where did you go?

I first landed in Jakarta because I had to deal with all my visa stuff. I lived in Yogyakarta, in Central Java most of the time and that was my home base. I lived with a couple who were faculty at ISI Yogyakarta, the art school in Yogyakarta. I also spent a lot of time in Bali, in a village called Bedulu, pretty close to Ubud in central Bali. I lived with a family there who I am still very close with and are very dear to me. I also spent some time, not enough time, but I spent some time in Sumba, because I felt I needed to go to that source of my original spark of interest. It was very hard to find people still using natural indigo dye in that region when I was there. Then traveled around a bit other places. But most of my time was in Yogya.

I love Indonesia. My time there has been so important, not only to my personal growth and my understanding, my art, my writing, my research. There is something that happens and I am sure you know this too, when you leave home and you go and you assimilate into a new culture, learn a new language, learn new ways of being and interacting with people, learning new cultures. It is so valuable to the creative process, to the intellectual process, to expanding one’s self understanding. So, I am so grateful for my time spent in Indonesia. Of course, it was really beneficial for me personally, in all those ways, but also I made so many dear friends there. They are so far away, but thankfully modern technology allows us to stay in communication.

My impression of Indonesia is that it is an incredibly diverse country. Someone described it as an impossible country, because there are so many different cultures, ethnicities, religions, practices, in all these islands all over. Everywhere that I visited, I was still amazed at the diversity of everyone and every culture that I visited.

It is not a place that I can think of as sort of a homogenous country culture, but the thing that I appreciated the most was how warm, inviting, hospitable and generous people are, it was amazing to me. Everywhere I went, I was welcomed. It was so easy to make friends so easy to get to know people because everyone was so open, curious and interested. It was really a pleasure to be the recipient of generous hospitality. It is such a gift.

And in terms of practices, what learning did you pick up from there?

I went with the hopes of learning, not only about textiles, batik, ikat weaving and indigo dyeing and other natural dyes. I did learn quite a lot from many people. But I also was really interested in getting to know the contemporary art scene which is part of why I chose to live in Yogya because that is really one of the sort of center for contemporary art. I think the arts are so diverse and complex because there are so many different ways that people are engaging in creative work. Someone who is still weaving a warp ikat in the same way as her ancestors and using the same dyes, someone who is making textiles in a very traditional and ancestral way.

There are also people who are creating these incredibly hybrid, strange and interesting things, to sell to foreigners. Things that are like quoting from traditional culture but are easy to make and sell. It is a sort of symbol of culture that you can share and make a good living. There are these hybrid things that there are artists working within the realm of the contemporary arts.

I guess what art means to me is artists who are making their artworks with the intention of showing it in galleries, international exhibitions, like the Yogya and Jakarta Biennale and hoping to show many people, of course, to show their art in the galleries in Singapore. That is a huge step in someone’s career. So, there are all these different ways that I was exposed to the creative process, which was really useful for me to reflect on what is the nature of creativity when it comes down to it. And to really think about the supposed differences between tradition and contemporary and where they meet. I spent a lot of my time hanging out in many art spaces and art collectives around Yogya which is how I came to understand about ”nongkrong” (hanging out) and how important that is.

Understanding nongkrong helps me to feel more of a sense of belonging in the culture around me. It is funny to say, to learn how to hang out. It was a learning process.

Maybe you might want to elaborate more about nongkrong.

Yes. So, for those who are not familiar with what nongkrong is. Somebody once described it to me, nongkrong is when you squat down by the side of the road, with your cigarette, and just hang out with some people and talk, and then you move on. It is like this temporary hanging out, casual, it is not scheduled, it just happens naturally. It is funny to me as an American researcher, I felt this pressure, because I had these important institutions funding my projects, I felt this pressure to produce something. But I kept finding all I am doing is hanging out all the time. I am just going to art shows and hanging out with people. It is really great. But what if I am not getting anything done, I am not working. But when I started to talk to people they are like, nongkrong is really important.

Nongkrong is how artists share ideas with each other when they are just hanging out. Maybe they are hanging out, having some snacks and coffee together or hanging out for an exhibition opening, but it became so clear to me that nongkrong, this process of just spending social time together, it is very nuanced. It is very important. It is sort of like glue that holds the art scene together. Some people described it as kind of like school, the good kind of school. You can learn things that you do not get to learn in actual school, by sharing ideas of friends. Many things I learned not only by engaging in nongkrong, but also starting to ask more questions about it and starting to incorporate that into my research. In the beginning, it was just hanging out and drinking coffee and chatting. Then they invited me to hang out with them.

I do not remember the exact context, but I think I was sort of describing, “I noticed that I am doing a lot of hanging out with people and people are always hanging out” and then someone was like, “that is nongkrong.” I was like, what does that mean? He then explained to me a little bit and I said, “Oh cool, there is a word for this.” And then, everyone started to talk about nongkrong. Once I had that basic understanding that someone had given me, then I just started asking people, “What does nongkrong mean to you?”, “and are we doing nongkrong right now?”, “or is it something else?”

So, every time I asked that, people got so excited. That was the research topic because they wanted me to be doing. They are like, you are interested in textiles and the sort of traditional and contemporary arts, that is interesting. But nongkrong, that is really interesting. It was so delightful and it was just really lovely. Understanding nongkrong helps me to feel more of a sense of belonging in the culture around me. It is funny to say, to learn how to hang out. It was a learning process. At first, I did not know.

Very interesting, you wrote the whole paper or article about it. I knew what nongkrong is. Probably as I have been in Singapore for a while where everything is so deadline driven. So, when I did my first batik trip, I had a certain KPIs (Key Performance Indicators). I have to spend probably two hours at one place so that I managed to cover a few artists or places to do my research. I mean, it just drags on and it is impossible to (complete).

Yes! You cannot have a schedule. That was interesting. That was really one of my early lessons in assimilation.

You mentioned earlier about Indonesia, there are artists who are using all these elements with roots based on ancestral practices and how they include it in contemporary arts. Can you elaborate more about it?

When I was doing my research online, before coming to Indonesia, I was finding information about the early contemporary artists, people who were coming of age in the 1980s and kind of making their more experimental artwork. Then into the 1990s and early 2000s. I had more familiarity with artists like Heri Dono is one of a very famous artists, and many others who I saw were incorporating images or materials, whether it be wayang, shadow puppet, or wayang golek other types of materials. Maybe taking parts of these kinds of traditional puppets and then creating something and incorporating them into an artwork, like a large installation that included other elements. And that was clear that they were using these particular materials or these symbolically important references to Javanese culture. Not just through wayang but through batik and traditional clothing.

The interesting thing to me was that it was clear that these were contemporary artists. So, they are using these materials not for the the typical function that they would be used for, but they were using them as materials, as conceptual materials, things that could tell a story, or that had an idea embedded, or maybe there was some element of cultural critique in their artworks and that they were using these kinds of signifiers of Javanese culture, for example. So, I was interested in that because it was clear that the context was contemporary art, but a lot of the materials were coming from historical art forms.

When I arrived with these kinds of things in my mind and these questions, and I started looking around and talking to younger artists, it sort of became clear that those kinds of questions were not as important to artists at that time. This idea of using cultural signifiers in their artworks was not always so important to people. People were just interested in making what they wanted to make. One person actually told me, those things are like the old guard of the contemporary arts they were interested in, but people are not so much interested in that anymore. I think that was partially true. I think there is still plenty of that kind of cultural mixing going on in the contemporary arts in Indonesia.

But I was interested in those things because at the time, I perceive that, in the United States, in a sort of realm of the contemporary arts, there was no lineage. There was no depth of roots of material and I was interested in reaching deeper. I wanted to be a part of something, a part of a lineage. In retrospect, I realize that much of that thinking was very naïve. Of course, there are lots of different lineages and roots always being made and continued but there is a feeling and I think we have talked about this a little bit before – this idea of the immigrant culture. Everyone should have come from somewhere else and all the roots have been cut off. So we are just in this weird situation of making up something new, sort of inventing something new, (as reflected) in the works that I made with my collaborators, Craft Mystery Cult and we are thinking a lot of those things.

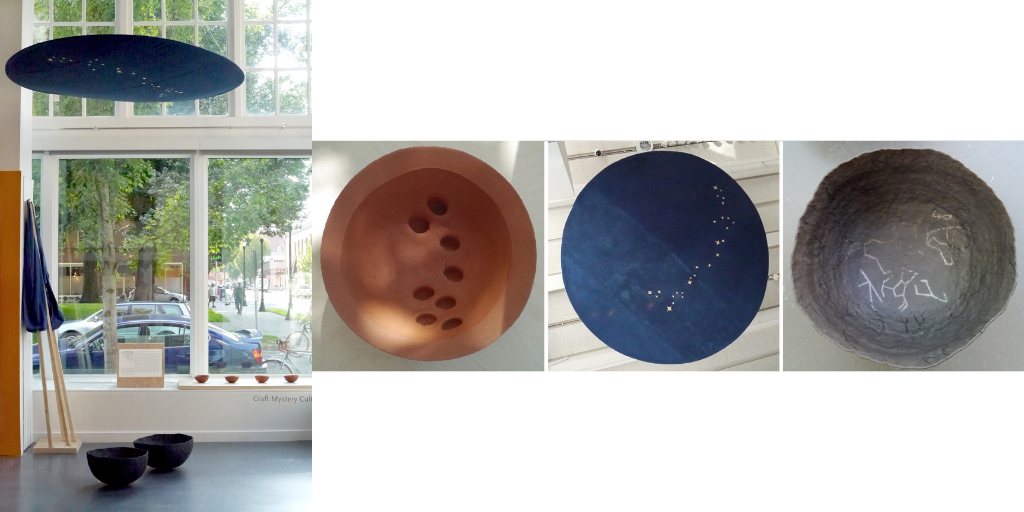

A Ritual Setting Involving Indigo Dye (2012)

One of the artwork that probably part of the results that you were in Indonesia and the one that caught my eye was entitled “A Setting for Rituals Involving Indigo”. I am researching at the moment about natural dyes cultures, specifically for batik. I heard that you went to Yogya and so I am trying to dig a little bit more about this work.

Yeah, that is still one, I think, the most important and special artwork that I was involved in making. I did not make that work alone. It was a collaboration and my collaborators Jovencio de la Paz and Stacy Jo Scott. We were all studying together in the same school and doing our Masters degrees. Jovencio and I both work primarily with textiles and Stacy Jo works primarily with ceramics. So, the three of us were really invested in and thinking a lot about craft. So in some ways I think when we talk about craft in the United States and in Europe in this sort of contemporary context, it is sometimes like a code word for “tradition”. Craft is a way of making things that have a deeper root.

We were interested in thinking about artistic craft, the roots of making, the roots of the creative process. We were really interested in these questions about a craft and I think that’s what led us to make that project, A Setting for Rituals Involving Indigo Dye, as our collaborative thesis project. So we were thinking a lot about ritual and also the sort of repetitive (actions). The nature of many of these kinds of media involving physical repetition. Many people say that weaving is very meditative, spinning yarn is very meditative, making pottery on a potter’s wheel is meditative. But what does that (ed.: meditative) actually mean? I think it means that people kind of go into a sort of relaxed mental state because their hands are busy, because they are doing something that is very pleasurable with their hands that involves physical materials.

We were thinking about all these different kinds of repeated gestures that are involved in craft media like textiles, ceramics, metalwork and woodworking, so that piece we created almost like a stage and populated that space with all these different symbolic and evocative objects that we just created intuitively.

There was a performance that would happen every single day in the museum. Someone would come in dressed in like a denim work shirt and black trousers. They would enter the museum, take off their shoes, step up onto the platform and then they would perform one of these kinds of repeated gestures that we came up with. They were not necessarily demonstrating how you dye something with indigo or how you make an object out of ceramics. The gestures were meant to sort of evoke the feeling of being involved in those kinds of ways of making, so they were kind of poetic.

Stacy Jo designed this beautiful porcelain vessel that was a water clock. So it is like an ancient. I think they were used as timekeeping devices in ancient Greece or something. There would be a tiny hole in the bottom of the vessel and you would know how much time had elapsed when the vessel was finally full and sunk into the water. So she created these water clocks that someone then would place into the indigo and then sit very still and watch it slowly sink, filled with indigo and sink and then she pulled it up, emptied it and then put it aside on these indigo-dyed mats that we had also created. We were sort of playing around with this idea of ritual, but we were not using any specific ritual ceremonial culture that any of us belong to. There was sort of inventing a ceremonial fiction. We wanted people to come away with it, viewing this with a sense that they were feeling something, that they were getting some kind of evocative feeling of the relationships with their own body and their own agency of making. It was a really special project.

It is really interesting. So, as you mentioned, it is just intuitive and there is like no particular symbolism that is portrayed.

We use some techniques that were maybe more culturally specific, for example, clocks that we had dyed. We made these little mats that the water clocks that they would sit on after they had come out of the indigo dye. Those were patterned with indigo using shibori techniques which are commonly associated with areas like Japan and West Africa. So different ways of making a pattern by folding or tying the cloth so that areas of the clock resist the dye, so it becomes a white and blue. So that was maybe the only sort of really clear link to any particular cultural art form, but otherwise, we were trying to just to design things that were in our imagination.

When you come to Indonesia, are there particular rituals that people have been using, related to indigo?

Well, I was curious of course to learn more about that, but the primary thing that I observed after spending time in different locations in Java, what I found mostly with that was people were trying to relearn how to use indigo dye – how to grow it, how to process the plant, how to make the dye fermentation work, how to get a good colour from it. A lot of people are really struggling with this. Because it is difficult, it is a living substance, it is moody. People talk about indigo having a mood, like a human. I can definitely attest to it from being a steward of indigo myself for many years. It is particular. If too much air gets into the liquid, then it will just stop. It just stops, no more blue and it will almost like I do not want to do this anymore. So it was interesting for me having training of using indigo dye in different contexts and then observing how people were using it, trying to relearn how to use it and for the most part people were interested in learning to use indigo again through sustainable practices and natural substances, working with natural dyes.

I definitely saw that there was a gap in the knowledge of how to do it. It had been interrupted in previous generations through the colonial enterprises, which is ironic because we are very interested in batik and imitating it, also very interested in Indigo Dye as an export substance, so it is interesting. That sort of happened.

In other places, I did see that there were definitely people who were still practicing indigo in the ways that their grandmothers and great-grandmothers had done that. There was this sort of unbroken chain, but I never spent quite enough time in any one place to really understand fully what the original culture was. So, I hesitate to try and make any assumptions, but for sure I did in some places, especially in Sumba and Flores, the places I have visited, people did share a little bit about the original culture around indigo, some of the rules and taboos.

In Sumba and Flores, woven cloth or Indigo or natural dye cultures are being passed down and mostly through oral education, so they just took apprenticeship with their parents or grandparents. I do not see a lot of that mentioned in the batik in Java. So, as you mentioned, there is this gap.

Yeah, I observed that there are things that have been lost. The knowledge that has been lost through time and that is because things are passed down through oral culture. There is a good reason to mourn for things that are lost in those ways. It makes it very hard for the people of the current generation who want to be able to make whatever it is that they no longer know how to make. It makes it very challenging, but there is something very exciting. There is a lot of energy and spirit of possibility. So, not only are people relearning how to do something the way it was done by their grandparents or great-grandparents, but they are also incorporating their own ideas and influences into it. So they are kind of making new things happen. I think there is something really exciting about that also.

What is your indigo ritual? It seems that it becomes a seed for you to explore other works, such as the other one entitled “I’ll Tie My Cloth To Your Cloth” (main image), one that incorporates batik.

That is another really special piece for me. It is the only artwork I have made with batik. Well, that was not true, I made the batik with the star constellations for the Craft Mystery Cult collaboration. But this was a piece that I made. I was thinking about sarong, that long piece of fabric that you wind around your body and that is the action of wrapping yourself. Like swaddling a baby, in a way, there is a tenderness to that kind of action of wrapping oneself in textile. Of course wearing batik can also be very constrictive, but I was thinking about it in a poetic way.

I was thinking about this kind of cloth that I spent so much time in my life in Indonesia, really trying to understand and listening to people share their stories of the significance of different kinds of cloth including batik. I was also thinking, at the time, about indigo dye as a substance that was used in mourning rituals. So if someone has passed away, oftentimes in many cultures an indigo dyed cloth is used to wrap their bodies or the people who are in mourning would wear a blue. In many cultures, like in West Sumba there was an association of the Indigo dye itself as being related to the life cycle. Indigo is a fermentation. It smells like a decay, so it is associated with a transition of death, a sense of loss. I was thinking about all these things and I was thinking about it in relation to how we as humanity are just really destroying this planet that we live on and rely on. We are doing a very poor job of being in a good relationship with the natural world. So I was feeling very sad and heavy about that. I think all of these things were in my mind and in my heart.

I went to a really amazing artist residency on the mountain in Oregon, and I had a cabin and studio, and I decided to make this work there. So, all the imagery that was on that batik cloth are related to ideas of transformation or regeneration or celebrating natural life cycles. So I created all this imagery and then I drew it on with the canting tool, trying really hard not to make any drips because I am not a skilled batik artist. It was really hard work to make that cloth and then I dyed it in indigo.

Then, I created a video component where I recorded myself, not only wrapping myself in the cloth, but also this little moment where I would be tying the end of my sarong to some significant objects, whether it was a small tree or the shoelaces of my father’s running shoes, he is always been a runner, or the roots of a tree.

I have that idea and the title comes from a story that I had read from Catherine McKinley who had been a Fullbright scholar and went to study about indigo in West Africa. She wrote this wonderful book about her experiences, titled Indigo. She was telling a story about her closest friend whose husband suddenly passed away. Through the process of mourning, she described an incident when a neighbor came over to visit the widow, who had just lost her husband, and she made this gesture where she knelt down and she tied the end of her wrapper cloth, the skirt which she was wearing, to the end of her friend’s cloth who had just lost her husband. She said something to the effect of: oh my friend, we are in this together, we are here together, let me tie my cloth to your cloth. I thought that gesture just really stuck with me when I read it. This idea of tying your cloth to another cloth is such a beautiful, poetic way of showing care, but also honoring the pain of loss, the pain of mourning because of someone who has died or at the time mourning the loss of animals and health of our environment and across the world. So that gesture and that little phrase from that story all about indigo, bubble up for me. I use that to tell a story, through making that cloth and kind of using or activating it, through repeated, ritualised gestures. I recorded these as video images and stills of tying the end of the cloth to something.

It is a really beautiful, symbolic way to show your ties and relationship with Indonesia and how the spirit lives in you.

For sure, that is why I said that piece is really special to me. I think one of the artworks that, maybe, has the most heart in it. There is a lot of my heart in it. It is sort of a warm feeling.

What are some of the ongoing projects?

Stacy Jo, Jovencio and I have been talking recently about. Well, we talk about this every now and then but I think we are really going to pursue an idea that we have had for a long time of remaking our original artwork A Setting For Rituals Involving Indigo Dye. To make that work again but in different ways. We have had this idea of traveling to different places where some of the people are our peers in graduate school who performed in that original artwork to visit them. We have some friends who live in Los Angeles. We have a friend in Oslo, Norway and Stacy Joe will be traveling there next fall, in the next November to make a collaboration with her. So, there are all these people around and then the three of us, of course, recreate the piece as a sort of traveling temporary exhibition and I love this idea. I am really excited about it. So, that is a related thing that is currently cooking.

I think it will be very interesting.

Any final thoughts to sum up our conversation today?

It has been such a pleasure. I mean in many ways, it is really a gift for me to be asked to reflect on these different experiences in my life, also some of these really important artworks that I have made and materials that I work with. It was 2012 that we made “A Setting for Rituals Involving Indigo Dye” together, so that is nine years ago. It has been a long time since we made that important work. It has been really nice and special for me to have a reason to revisit those things. I think it has opened up a lot of new ideas.

But also, all the things that I have been talking about, the experiences that I have had and things that we think about in my own artwork, all of that informs how I teach also. I think that is an important thing to maybe mark my relationships with Indonesia. Things that I have learned there, all of that, it is processed in my own mind, imagination and heart but it also has all really influenced my teaching and broader perspectives that I have gained through those amazing experiences and living in another culture and I am able to pass on to my students in some ways too which I am really glad.

Again, there is an oral culture and I am involved in an oral culture, I feel, as a lecturer. Maybe that is an overly optimistic thing to say, but in some ways, I am talking to them, I am sharing stories and sharing examples of artwork and I feel like that is a really wonderful and important way that I can continue giving, the gift that has been given to me by so many people.

Thank you so much Sonja for taking some time to nongkrong today

Thank you so much Tony, it has been such a pleasure, really nice to spend the time with you in this conversation.

Here are some of Sonja’s other indigo artworks:

Treshold (2015) by Sonja Dahl, exploring the the lifecycle and impermanence of fermentation parallel of indigo and bread.

A Setting for Leo, Lynx, Cassiopeia, and Camelopardalis (2013), in collaboration with Craft Mystery Cult.

We hope you enjoyed this episode of aNERDspective. Check out the previous episode on IGTV and our gallery and store if you would like a piece of Indonesia for your home or wardrobe. You may also check out Sonja’s website for the latest updates.

Photo credit: Sonja Dahl, unless stated otherwise.

CONTACT US | TERMS OF USE | PRIVACY POLICY

© 2024. NERD VENTURES. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

0 Comments